Anthropology News Column

by Aaron Ansell

In late 2016, I noticed a peculiar convergence between Brazilian and US politics. In both countries, the political right spurred mass mobilization against a ruling center-left party through the demonization of leading women as corrupt. While neither Senator Hillary Clinton (US) nor President Dilma Rousseff (Brazil) were indicted on criminal charges, these accusations helped to bring about drastic changes in each country’s government. In Brazil, where I’ll focus my attention here, popular allegations of Rousseff’s corruption had previously emboldened the congress to impeach her based on “an eclectic bunch of reasons” often having nothing to do with the formal charges (The Economist 4/18/16). Here I suggest that anti-Rousseff urban demonstrators, along with a few of my own field consultants in Brazil’s rural hinterlands (Piauí State), convinced one another of Rousseff’s guilt through a meta-communicative process that equated disparate, poorly evidenced aspects of Rousseff’s venality.

Brazil’s legislature impeached Rousseff in August of 2016 for what many saw as a relatively minor and commonplace act of administrative malfeasance (BBC News 8/31/16), though she was simultaneously accused in the media of more serious forms of corruption (see analyses by Perry Anderson, Glen Greenwald, and John Gledhill). Many on the political left reckon the impeachment as a second, right-wing “coup” (golpe) analogous to the 1964 military seizure of the executive. For sociologist Laymert Garcia dos Santos, the impeachment inaugurated a “state of exception” in political theory terms, that is, a moment when sovereign power declares a national emergency to halt the normal procedures of representative democracy.

Looking at popular allegations of Rousseff’s corruption, I suggest that practices of “iconization” have been central to an alternative regime of evidence-making that has pushed centrist Brazilians toward a pro-impeachment posture. Generally, iconization refers to the manufacture of resemblance between character traits and forms of expression, for example, interpreting a dialectal drawl as a sonic manifestation of southerners’ laziness (see Irvine and Gal 2000). In this case, Rousseff’s detractors manufactured resemblance (and imputed shared origin) among behaviors that spanned multiple characterological domains, including sexuality, criminality, ideology, and policy proclivity.

Listen to how Tomás, one of my right-wing consultants from rural Piauí State, talks about Rousseff.

She’s totally corrupt. Totally dirty. Do you know that right here in Passerinho, many people get Bolsa Família who don’t need it? She’s a dyke (sapatona). She’s an assassin, a terrorist. The military men even put her in prison. She’s a communist. I’ll never vote for that dyke. You can throw her in jail.

The verbal parallelism among each of these accusatory features creates a network of mutual validation so that no single accusation requires independent evidence. This discourse-internal evidentiary structure portrays Rousseff’s persona of corruption as a gestalt arising out of a mosaic of seemingly analogous behaviors and identity features.

Throughout months of anti-Rousseff street (and virtual) protest, demonstrators’ signs, carnival floats and internet memes displayed a similar evidentiary logic. Certainly, a range of parodic internet memes reiterated Tomás’s claims about Rousseff’s corrupt policies (“many people [“of means”] get Bolsa Família who don’t need it”), and her venality (“dirty”), homosexuality, and criminality.

In the cartoon below (Image 1), President Rousseff sits behind a desk with a voting machine marked “Re-election” as she assures a mother of seven that her anti-poverty stipend, Bolsa Família, will not be cut off. “What a scare my husband had,” says the mother, “He thought he’d have to go back to work.”

Image 1

The cartoon imputes a characterological resemblance between Rousseff and the welfare mother, despite their obvious stylistic differences: Just as the mother is cheating the government because her family is not truly needy, Rousseff is cheating the nation by distributing Bolsa Família as compensation for votes. More subtly, the two women deviate in inverse fashion from the norms of proper womanhood. The cartoon figures the welfare mother as oversexualized by implying that her children come from multiple fathers (as the children’s variously racialized appearances indicate). Inversely, Rousseff’s dress and severity of gesture masculinize her so as to make her insufficiently (hetero)sexual (a complement to frequent snickers regarding her status as divorcé). Indeed, media critics often deride Rousseff’s style as clinical, callous, inauthentic, and wonkish, not unlike Hillary Clinton.

Degrading images suggesting Rousseff’s improper femininity often appeared in conjunction with exaggerated claims about her “communism.” In the meme below (Image 2), a photo-shopped image of a cigar-smoking, camo-wearing Rousseff appears to the left of a photo of her alleged (female) lover. The use of a common imagistic trope, the combat-boot wearing foquista (urban guerillas from the military dictatorship era), manufactures a physical resemblance between homosexuality and communism.

Another meme’s use of tropic imagery mobilizes an actual photo from Rousseff’s 1970 arrest to equate her former political dissidence with that of a “thief.” Here (Image 3), her mugshot is featured beside that of her predecessor, President “Lula” da Silva, also of the Workers’ Party. (The military had arrested “Lula” in 1980 for subversive union organizing.) The caption reads, “Pretty, eh? Brazil’s elected presidents are also the bosses of the nation’s biggest crime and corruption gangs.”

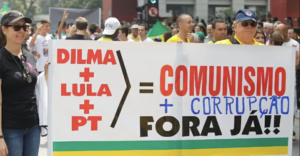

The various memes’ imagistic tropes work together to mutually construe a resemblance between left-wing political practice and various forms of deviance and venality. These linked features are first related through a chain of association based on logical extension (from anti-poverty policymaker to “communist”) and then reanalyzed as icons of one another, equivalent because, at heart, they are the same. The protest sign below (Image 4) expresses this equivalence in the register of mathematical certainty.

Gal and Irvine write that iconization “entails the attribution of cause and immediate necessity to a connection… that may be only historical… or contingent” (Irvine and Gal 2000: 37). In other words, things seen to resemble one another are easily imagined as ontologically identical. And so the evidentiary regime of right-wing corruption allegation implies that if even a single accusation (homosexuality, criminality, state clientelism, and so on) is verified, the rest must be true (and the facts simply await discovery). And because this logic paints Rousseff as polymorphously abominable, her presidency presents a total social threat that demands the suspension of the normal proceedings of democracy, even at the risk of their permanent suspension. Thus, a nation that has leaned to the social-democratic left for nearly two decades now seems to harbor what some journalists have called “A New Nostalgia for Military Dictatorship.”

Image 5

![]()

Image 6

To conclude, it’s worth noting how in both Brazil and the United States, the emerging popular right has depicted its targets in jailbird motif, a farcical aesthetic rendered menacing by chants to “lock her up” in the US and similarly in Brazil (see Images 5 and 6). In Image 5, the “13” on Rousseff’s uniform codes for the official number of the Workers’ Party, a little touch that betrays just how this structure of accusation works to criminalize membership and ideological affinity with a political party. This discursive process is a recipe for turning one’s loyal opposition into enemies of the state.

Aaron Ansell is an assistant professor at Virginia Tech.

Please send your comments, contributions, news and announcements to SLA Contributing Editors Anna Babel (babel.6@osu.edu) or Ilana Gershon (igershon@indiana.edu).